| INTERVIEWS A CLOSE SHAVE Interview: Alice Fowler Portrait: Polly Borland Night and Day (The Mail on Sunday) 13th May 2001 |

Everyone on the flight last December - including his wife, Lucy, their three younger sons and fellow passengers Jemima Khan and Lady Annabel Goldsmith almost died. Today, when Ferry, who had been heading off with his family for a quiet holiday in Zanzibar at the time, talks about what happened, it is with characteristic restraint. 'It was obviously scary,' he says, looking tortured. 'Every flight I go on there is always some bump or other.'

This, though, was more than just a spot of turbulence. Did he have time to think about what could happen? 'I can't remember,' says Ferry, fiddling furiously with the back of a chair. 'You tend to focus on your feelings afterwards-of feeling glad to be alive. I didn't think my number was coming up, quite frankly It didn't feel as if it was the right moment to die.'

In the terrible moments as the plane plummeted, passengers began to scream and pray. Ferry, as his 15year-old son Isaac revealed when the plane eventually landed safely, had other things on his mind. 'Everyone was freaking out everywhere,' he said. 'Except Dad, who told me to stop swearing.'

For Ferry, once a futuristic rock star, now a conscientious father of four, cool has always been more than skin deep. As part of Roxy Music, he was, to a generation, the epitome of ironic, self-conscious yet bedazzling style. From the start of the Seventies, through to the early Eighties, his band produced hit after hit - Love is the Drug, All I Want is You, Avalon - catchy, half-drawled anthems, oozing urban sophistication and visual flair. At their heart was Ferry himself: improbably handsome, with - for a while at least- Jerry Hall on his arm. If anyone would keep his head in a disaster, Ferry would be your man.

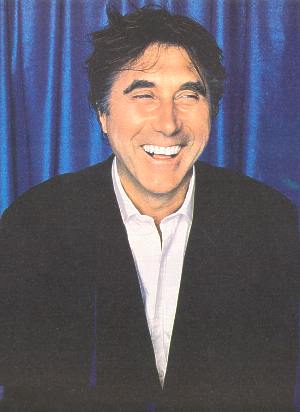

Today, almost unthinkably, Ferry is middle-aged. When

we meet, he appears every inch the family man, in blue jumper and trousers that

look suspiciously like chinos. For all that, he is tall and broad, with hair

that Still tumbles wildly: At 55 he is, in short, gratifyingly good-looking,

despite a distinct disdain for eye contact. Like most of his fans, I would be

happy to pretend he is not a day over 30, were it not for the fact that Ferry

can't help reminding me how old he is. He harks back to the days when there

were only two television channels; describes how he discovered Eminem while

moving the dial from Radio Four to Radio Three; and says 'in my day' at least

three times.

Today, almost unthinkably, Ferry is middle-aged. When

we meet, he appears every inch the family man, in blue jumper and trousers that

look suspiciously like chinos. For all that, he is tall and broad, with hair

that Still tumbles wildly: At 55 he is, in short, gratifyingly good-looking,

despite a distinct disdain for eye contact. Like most of his fans, I would be

happy to pretend he is not a day over 30, were it not for the fact that Ferry

can't help reminding me how old he is. He harks back to the days when there

were only two television channels; describes how he discovered Eminem while

moving the dial from Radio Four to Radio Three; and says 'in my day' at least

three times. If he sounds like your grandfather, you can hardly blame him: Ferry may be keen to emphasise his age before anyone else does. Next month, 18 years after Roxy Music broke up, the band will reform for a pension-boosting 50-date world tour. Oboe player and saxophonist, Andrew Mackay, and lead guitarist, Phil Manzanera, are back on board; so, it has just been announced, is drummer, Paul Thompson.

It is a bold move for a band which has never dwelt on what might have been. Ferry has gone on to a long, though arguably a rather less accomplished, solo music career, Mackay is a film and television composer, while Manzanera is a respected session guitarist and record producer. There have been many requests for the band to get back together; only now, they say, has the time been right. Another factor in the decision to reform is, undoubtedly, money. This summer, fellow mature rockers Bill Wyman, Neil Young and Ringo Starr will all be back on the road. 'I'm not doing this just for money,' says Andrew Mackay. 'That's not to say I am doing it for free.' Such nods to convention seem out of place to a band that has always excelled at being different. In the early Seventies, when rock bands were rough and denim-clad, Roxy Music wore space-glitter and used synthesizers. When punk began to shock, they became smoother and less abrasive. In leopardskin jumpsuits or snowy white tuxedoes, their style seemed as vital as their music.

For Ferry, in particular, the look was all. His passion was the 'artwork' - the series of striking album sleeves of semi-clad women, sprawling provocatively. For the fifth album, Siren, he chose Jerry Hall, depicted as a mermaid. Soon afterwards, she moved into his Los Angeles mansion.

She was 18, he was 30; and, for two years in the mid-Seventies, they became a gossip-column fixture. Pictures from the time show a grinning, mustachioed Ferry, his arm around a curvaceous, camera-courting Hall. The romance ended in a blaze of embarrassing headlines, when Hall, instead of joining Ferry in Switzerland as planned, went off with Mick Jagger. 'That was it,' she said later. 'I behaved badly No excuse.'

Even 25 years later, it is partly for this romance - and the public cuckolding by Jagger - that Ferry is remembered. He, in turn, battles to change the subject. How I ask, did it feel to be in the limelight? 'Mmmm,' says Ferry, looking pained. 'Funnily enough, music wasn't written about much in the papers at all. It only really featured in Melody Maker and NME, the music weeklies. There weren't style magazines the way there are now.'

What about the newspapers that revelled in their romance? 'Records were never reviewed. The gossip columns were just starting,' he continues, doggedly rewriting history. In 1982, Ferry wed society beauty Lucy Helmore; with her looks and breeding, she seemed to have all the qualities he coveted.

Again, it seemed as if he were immersing himself in a world which - by birth at least - was alien to him, but which he was determined to make his own. Meet Ferry today and it's clear his life has been one of extremes: on the one hand, the wealthy aesthete and man about town; on the other, a boy who grew up in abject poverty. If much of his life is shrouded in mystery, it is Ferry's child-hood that he will describe with rare fluency.

He grew up in Washington, County Durham, the son of a farm labourer who later worked down the pit. Money was short: Ferry and his two sisters, one older, one younger, grew up unexposed to the fripperies of fashion. Where, I wonder, given the constraints of his childhood, did his stylishness come from? 'I always thought of Fred Astaire and Cary Grant - both style gods - who came from humble beginnings,' he replies, seriously.

'Perhaps it means you show more interest. At a certain age I became interested in how I looked. I was keen on art at school, when I was 13. Before that, from about the age of 11, I was a music fan. At that time, there were no video games to distract me: I could lose myself in music - jazz, blues, that kind of thing.

'Then I worked in a tailor's shop on Saturdays, whiling away the hours looking through books with wonderful illustrations of gents getting out of Rolls-Royces in fabulous suits.

'Gentleman's tailoring is all about detail, really: how wide the lapel is, how many buttons, whether it is boxy or double-breasted, or this or that.' Suddenly the languid Ferry is transformed, tracing the intricacies of tailoring with his hands.

'I've always been known for it,' he adds, 'though for years, I didn't really bother about what I was wearing.'

Really? He nods solemnly. 'I've only recently got back into Savile Row and the whole idea of the British craftsman. It's rather nice to support that. I also like [designer] Tom Ford, even Armani - they have respect for that tradition of excellence. Men's clothes have become rather good again.' For a brief moment, he looks dis-tinctly happy.

At the same time, it's clear that an appreciation of tailoring is not something he would have learned at home. 'Not really, no,' he agrees. 'My background was incredibly simple, really humble, which I'm very thank-ful for. It's not as if I don't like my origins. I feel very strongly about them.

'My parents thought my childhood was incredibly well off compared with theirs. They lived in houses with-out electricity or running water, breaking the ice before breakfast. I loved hearing those stories. When my dad was courting my mother, he lived in the country and she lived in the town. Dad used to ride to see her on a plough horse, wearing a bowler hat and "spats". That embarrassed her terribly.

'They courted for ten years, because he didn't have enough money to marry her. Eventually they did marry and lived in a little farm cottage. He was a farm labourer and used to win medals for ploughing.

'Then it was the Depression. Things got so bad that my father had to go to work down the mine, looking after the pit ponies. It was a country job, but under-ground. It must have been awful for him. He earned a pittance of a wage - much less than a regular miner. He gave it all to my mother, and she'd give him tobacco money for his pipe.' He pauses. 'We could only get more well off after that.'

His parents were keen for him to go to college or university. When he did, winning a place from Washington Grammar School to Newcastle university, it was to study art. What did his parents think? 'They thought I was crackers,' he says. 'I remember Dad sitting there with his pipe, shaking his head. My parents wanted me to have a proper job - to be a lawyer or a doctor. But, at a certain point, they knew I had to follow my desires. Then, when I graduated and said, "I want to be a musician", they thought that was odd as well.

'They didn't understand what I was doing for a long time. They must have been amazed when I told them, "Oh, I've got a record coming out", and then they heard it on the radio.'

Were they proud? 'Oh God, yes. My mother would follow the charts. Dad was more out of touch; he never even used the telephone, really. He was quite old-fashioned, which was endearing, whereas my mother was really switched on.

Later, when his career had taken off and he left London for a country pile in the West Sussex countryside, Ferry asked his parents to live with him. 'They moved to the South to be near me, and spent the next ten years or so there. I think they had a nice time, despite missing their family and friends.

'But if I'd said, "Come and live at the North Pole", they would have done it. They were really wonderful people.'

I ask whether growing up in such poor circumstances sharpened his awareness of design and style. 'We didn't have a telephone or fridge or car. I suppose that gave me a sense of motivation for material things,' he says.

'I've always felt quite happy that I made a career out of something that brings some sort of pleasure to other people. Luckily, I didn't become a speculative builder or something like that.' He pauses, and I realise this may be the nearest Ferry comes to a joke.

Studying fine art at Newcastle, he was taught by the pop artist Richard Hamilton, whose influence would later spawn the 'covergirl' look of the Roxy Music album sleeves. After graduation, Ferry won a scholarship and moved to London, where he worked as an artist in the East End. 'I then started teaching and also restored antiques - that was my first experience with old furniture. I worked for a marvellous old soldier, Colonel Freeman, who had a shop on Walton Street, south London. He was a gentleman farmer from Suffolk. He'd say, "See what you can do with this mirror",' Ferry says, scrubbing the table furiously in demonstration.

He also started to write music. 'By that time I was teaching two days a week, and writing and rehearsing, putting together the band that was to become Roxy Music. It was very exciting, really,' he says flatly.

By 1971, the band was in place; their first album, also called Roxy Music, came out at the start of 1972. 'Really exciting it was,' says Ferry, trying again. 'Suddenly I'd found what I'd been born to do. It was much more physical than painting, and yet you could get all your ideas of form, arrangement and colour into music. And ideas. I had a lot of stuff waiting to pour out.'

For a decade, the ideas came thick and fast, casting an influence which can still be heard in the music of Radiohead, Pulp, Suede and Moby.

Gradually though, over eight studio albums, the spontaneity of Roxy Music seemed to falter; their music, once so innovative, seemed blander. There were tensions within the band, as Ferry's role became more prominent. Then, in 1983, when - commercially at least - they were riding high, Roxy Music decided to split. 'I got tired with the idea of being in a group,' says Ferry.

'We'd broken through with Avalon: that felt like a high spot. It was time to do something completely different - something on my own. I had lust got married, and I had other interests, other responsibilities.'

His marriage to Lucy has been enduring, but their life together has not been problem-free. In the Eighties, Ferry was brought low by depression and, in 1993, his wife admitted that she had received treatment for drug and alcohol addiction.

Their four sons - Otis, 18, Isaac, 15, Tara, 11, and Merlin, ten, have clearly been a great source of happiness. 'It's great having four children, four sons,' Ferry says, with rare animation. 'They can be a bit of a handful, but they are very amusing.'

Isaac and Tara are displaying their father's eye for style. 'Rather worryingly,' adds Ferry, a trifle unconvincingly.

Otis now works for the Middleton Hunt in Birdsall, North Yorkshire, looking after the hounds. Ferry is reluctant to say more, after fears that anti-hunt protesters may try to disrupt the Roxy Music tour. Still, his admiration for his son is evident. 'He's a wonderful boy. He's always been dedicated to nature. He never enjoyed being cooped up in school; he was always looking out of the window at the birds and the trees. It's great to see someone who so very passionate about the natural world.'

One of the remaining three, he thinks, may go into films. 'Not as an actor, but behind the scenes. I'm not sure any will go into music, though: it's hard to follow in your father's footsteps.'

Ferry's own musical career has not always been straightforward. When Roxy Music parted, he laboured on a series of intermittent solo albums.

'I got into a strange, underground existence,' he admits. 'I didn't think I'd tour again. I thought I'd just be a recording artist, doing weird and wonderful things in the editing studio. I didn't have strong enough deadlines. I found myself working endlessly on projects I could never finish. I became too fussy, chasing holy grails.' N

New albums did appear - Boys and Girls did well, he says defensively - and, in 1999, his collection of standards from the Thirties and Forties, As Time Goes By, was a surprise hit. But nothing has compared with the success of his early career.

A greatest hits album, The Best of Roxy Music, will come out to coincide with the tour; Ferry has another solo album in the offing which - behind schedule as usual - is due to appear early next year.

The tour, he concedes, has a certain poignancy. 'I have flashbacks to when I was sitting there writing the songs. You don't forget how you felt, but it becomes more complex. It's a whole lifetime since I wrote these songs. The audience is bringing memories of when they first heard our music; hopefully I'll revisit the feelings I had when I wrote the songs.' Has that life been fun? 'Parts of it,' he says, a little grudgingly. Yet, while he makes light of his recent brush with death en route to Nairobi, other events have made him think more deeply about his own mortality. A far worse moment, he says, occurred last year when one of his best friends, Simon Puxley, died.

'He was a big part of my life in music: he wrote the sleeve notes on the first Roxy Music album cover,' he remembers, with emotion. 'He was like the fifth Beatle: a part of Roxy Music who was always there. He was a beautiful writer, a doctor of philosophy and of English literature. He worked with me every day. He would have been on this tour. I keep asking him, "Is this the right thing to do?", because I am so used to him being here. He died of cancer, as my mother did. He was someone of my generation, so, when he died, it was much scarier than what happened on the aeroplane. When people ask, "Has it made you appreciate life more?", I say, "Of course", but I had already been through this with my friend.' Puxley, he says sadly, died on the first night of the American leg of the As Time Goes By tour; Ferry, to his obvious regret, was unable to attend the funeral.

It is a rare moment of revelation from a man who, these days, has made reticence a new kind of art form. Quickly, he rallies and starts talking about his tour again. His politics, he maintains, are no different this time round: 'I've never taken any political decision really; I just pretend to be violently right wing, just to annoy people.' Surely today's chino-clad Ferry is more conservative than the innovative rock star he once was?

'I don't really get older,' declares Ferry, with an air of finality. Cutting-edge performer or self-deluding dinosaur? Next month we, like Ferry's children, have the chance to find out.